by Andy Perkin

(written for "Adapt the Nothing" compiled by Nicola Winstanley)

In a city that has been codged together from a line of pottery towns, it would be easy to dismiss Middleport as just another outlying district along with scores of others. But Middleport has a fascinating history – one that finds its place in the middle of an industry, the middle of a transport revolution and, eventually, the middle of several regeneration schemes.

Middle of what?

Anything named after the middle of something needs edges or ends. In this case, Middleport lies between Longport and Newport on the Trent & Mersey Canal. None of these names are particularly old and would have been unfamiliar to local people 250 years ago. At that time, just over a mile to the north of this place, work had begun on the longest transport tunnel ever attempted. Overseen by James Brindley, navigators (about to be christened “navvies”) took their shovels and barrows to make a hole through Harecastle Hill. Soon would come the boats and cargoes which would turn a few local potteries into a world-renowned industry.

The canal milepost at Newport informs us that we are 34 miles from Preston Brook and 58 miles from Shardlow – the former being a village near the west end of the canal joins The Bridgwater Canal on route to the River Mersey and the latter a village near the east end and the junction with the Trent. A quick calculation makes us 12 miles from the middle. But the ends, and the maths, are unimportant. For the group of pottery entrepreneurs that financed the cut, the Trent & Mersey was never intended as a through route – it was all about getting raw materials into, and finished ware out of, The Potteries. For many of them, this mile of canal clinging to the side of the valley above the Fowlea Brook was the middle.

Ideally, they would have liked the canal to pass in front of their factories in the pottery towns, but the topography – and the need for a generous supply of water at the summit – meant that Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Fenton and Longton were passed by. For the Mother Town of Burslem, the closest practical approach was to be at the tiny hamlet of Longbridge, where the old highway to Newcastle crossed the brook. The name apparently came from a footbridge of planks around 100 yards long next to the ford, but was dropped in favour of Longport when the canal opened in 1777.

From the outside in

For the eighteenth century industrialists, Longport was the place to be, and the land adjacent to the new canal bridge was quickly snapped up. Brindley’s brother established the Longport Pottery to the north and the land to the south of the bridge bought by his brother-in-law, Hugh Henshall, who established Longport Wharf and The Duke of Bridgwater inn. Other potteries took the prime spots, many of which were absorbed into the ownership of William Davenport by the end of the century. Davenport developed a further pottery, together with a grand house for himself, three-quarters of a mile south and named the area Newport.

For the eighteenth century industrialists, Longport was the place to be, and the land adjacent to the new canal bridge was quickly snapped up. Brindley’s brother established the Longport Pottery to the north and the land to the south of the bridge bought by his brother-in-law, Hugh Henshall, who established Longport Wharf and The Duke of Bridgwater inn. Other potteries took the prime spots, many of which were absorbed into the ownership of William Davenport by the end of the century. Davenport developed a further pottery, together with a grand house for himself, three-quarters of a mile south and named the area Newport.

Land by the canal continued to be much sought after, particularly the east side – closest to the town and away from the towpath. South of Westport and between Longport and Newport was to be a new wharf, to be named, appropriately, Middleport.

Branching out from the middle

This new development did not go unnoticed in Burslem, where the pottery manufacturers still struggled to get their raw materials into town by barrow and packhorse. A thirty-ton shipment of ball clay or flint, that could be pulled by a single horse by narrowboat, would have taken nearer 60 trips by packhorse. Josiah Wedgwood had already left to set up his Etruria factory to take advantage of a canal-side site.

As part of the Trent & Mersey Canal Company’s strategy to forge better links with the pottery towns and Newcastle-under-Lyme, a new half-mile branch canal was to be cut alongside Dale Hall Brook to a new wharf, from where goods could be transported to onto a rail- or tramway to the town centre at St Johns Square. Completed in 1805, this tramway predated steam and electricity and relied on horses to pull the wagons on cast iron rails. Until the arrival of the North Staffs Railway and the Potteries loop line 60 years later, the arrangement remained the best way of moving heavy goods in and out of Burslem, the canal branch surviving until a breach in 1961.

A home in the middle

Writing in 1843, John Ward, only refers to Middleport as the name of the wharf rather than a place. It seems that in the early days, people made their way from Burslem to work in the newly established factories, mills and wharfs that lined the canal, while very few called Middleport their home. With the coming of the branch canal, a triangular community emerged defined by the two watercourses and Newcastle Street. William Davenport was among the first to invest in new terraced housing, which was complemented by a chapel and a park. A network of traditional terraces streets grew throughout the nineteenth century, until hundreds of homes filled the spaces between the canals and factories.

The basic two-up, two-down terraced housing was ubiquitous into the twentieth century and worked well. Fronts-facing-fronts across uncluttered streets provided good surveillance and backs-facing-backs enclosed private spaces for washing and drying clothes. Ongoing wear and tear gave rise to selective rebuilding, which commenced with those streets immediately to the south of Newcastle Street. Here concerns about the increasing use of the motor car and the perceived need to separate pedestrians from trafficked areas, led developers to adopt Radburn-style housing layouts, pioneered in America. Much-reported catastrophic failures of the model from abroad did not deter local developers from repeating their mistakes as regeneration swept through Middleport, right up to the 1990s.

The lowest point came at the start of the next millennium when an ill-fated housing renewal scheme set up on the wrong foot – demolishing relatively robust terraces rather than their poorly designed neighbours – and left empty spaces and displaced families when recession bit.

From the bottom up

Fortunately, by this time the community had decided it had had enough of being done-to, that the cavalry was never going to arrive, and local people needed to take matters into their own hands. Early adopters of this bottom up approach were Burslem Community Development Trust (BCDT), working with local partners.

Fortunately, by this time the community had decided it had had enough of being done-to, that the cavalry was never going to arrive, and local people needed to take matters into their own hands. Early adopters of this bottom up approach were Burslem Community Development Trust (BCDT), working with local partners.

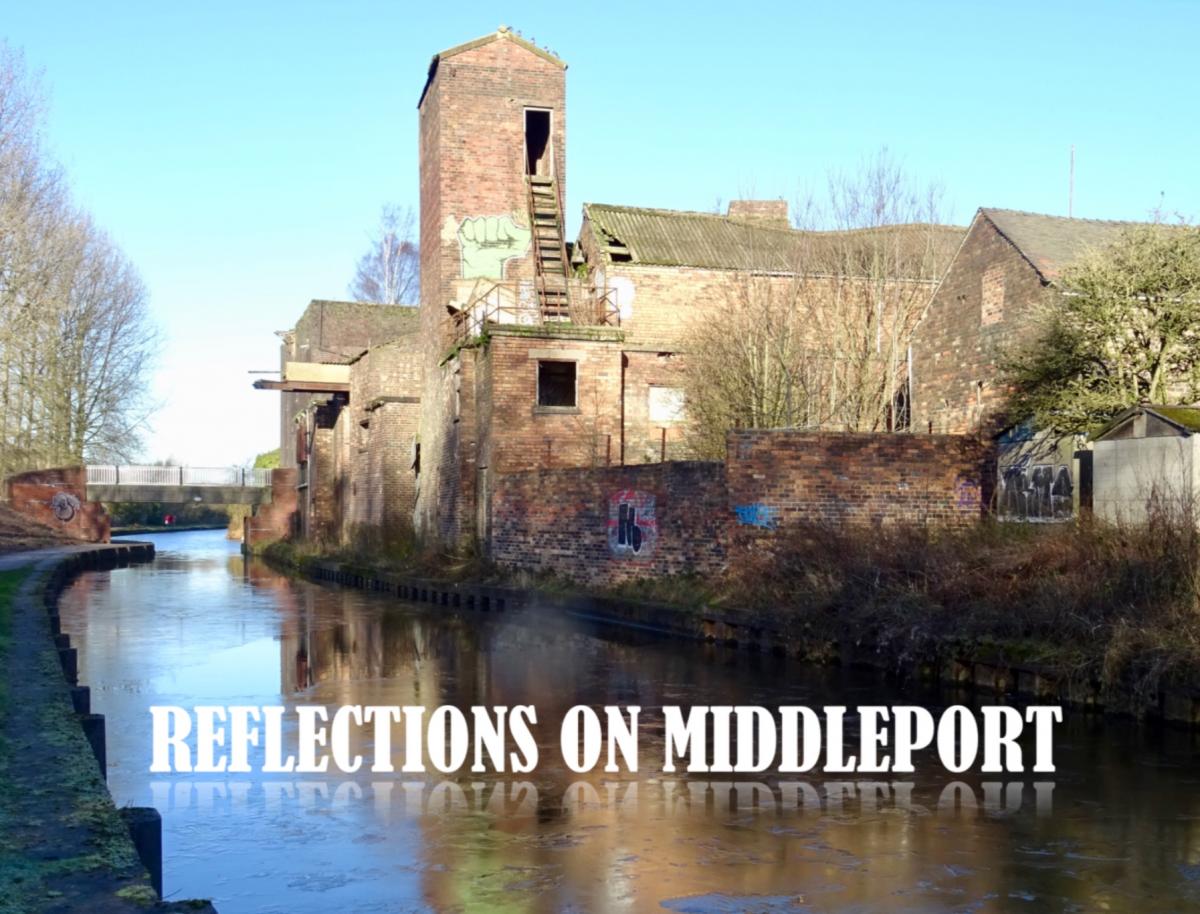

With the Trust’s support, Middleport Environment Centre campaigned for and acquired (for a time) the derelict Port Vale Flour Mill, from which they ran North Staffordshire’s first curb-side recycling scheme – long before local authorities were obliged to offer the service. As Middleport Environment Trust, the group still supports local initiatives.

Also with the help of BCDT, an ambitious plan was hatched to restore and reopen the Burslem Branch Canal. The project has been hard fought for by the Burslem Port Trust over two decades now, but their ideas are finally chiming with regeneration agencies and work is starting with a view to re-establish the lost towpath and level the land.

Middleport still matters

Further regeneration has centred around the welcome renovation and resurgence of Middleport Pottery, complementing the historic Burleigh factory with enterprise units and a heritage centre. The work was initiated by The Princes Regeneration Trust and the attraction is run by the UK Historic Buildings Preservation Trust with support of local volunteers.

By far the most promising initiative to secure a bright future for the area has been the Middleport Matters community organisation. The group started small with regular litter picks and activities for parents and children, but quickly gathered momentum. Constituted in 2017 as Middleport Matters Community Trust, it has a vision for the area as a “safe, thriving and welcoming place for everyone” and aims to bring this about by bringing people together, improving health and wellbeing, enhancing the built and natural environment, and supporting local enterprise. The group has already initiated the local neighbourhood plan and aspires to tackle derelict buildings and set up community housing projects.

Thriving and welcoming encapsulates the spirit of Middleport, where the current highway project is to connect underused land near Newport directly to the A500 duel carriageway. Let’s hope that this latest infrastructure project helps make Middleport’s future as significant as its past.